Context:

IGD900: Guided Research Project

Setup:

Oculus Quest + Unity + Oculus Integration + Leap Motion

I\ Introduction:

The IGD900 Project is a guided research project offered by the IGD master program that I’m currently following. It is an opportunity for me on a personal level to discover the work environment in a research context and to assess whether such a career direction will suit me. For this purpose, I contacted my tutor Jan Gugenheimer and we discussed different subjects related to the mixed reality field. We agreed finally to work on developping a new VR interaction technique aiming at improving on the work done in the world in miniature (WIM) paradigm and to add to it a proprioception element.

II\ Main idea:

One problem that is still an open research question in VR is the interaction with remote objects. Different kinds of interaction can be needed like selecting, spawning, activating, scaling or moving objects. To design solutions for such situations, one need to consider a lot of factors like speed, precision, learnability, acessibility,… Multiple VR interaction techniques have been and are being proposed and they all address such constraints and must be thought of in the context of a trade-off.

For this reason, I would like to start by defining the context of this new interaction tecnhqiue. The aim is to enable the user to select and activate objects in medium-range in a way that fully tap into the three-dimensionality of the environment while still achieving good speed and presence performances.

‘Within Hands’ Reach' operates as a World-in-miniature metaphor while still immersing the user in the interaction area. This is achieved by mapping one of the user’s hand’s movement (H1) on a virtual giant hand that sits under the VE. The user can observe a transparent figure of this hand appearing and moving under the VE and can pinpoint precise positions and objects. With the second hand (H2), the user can interact with the pinpointed object/position by interacting with the corresponding area on his physical hand (H1).

III\ Advantages:

This technique is based on the hypothesis that the proprioception element would allow for better presence and faster interaction time. This is a potential improvement on the WIM techniques where the user focuses on the miniature in order to perform precise actions.

The speed performance advantage counts on the fact that it would be faster for the user to pinpoint a finger or a cetain area on the palm than to count only on visual clues like in the case of ray casting techniques. When ray casting, the only input the user has is a visual one: the relative position of ray in relation to the virtual element to pinpoint. Movements are performed fully with regard to their mapped equivalent in the virtual space. The user would be moving as they perceive movement in the VE and not as it is perceived in the real world. If I percieve a button that I should press one meter far from me to the left, I should move my hand the amount of distance that should give one meter in that VE and not one meter precisely. This may lead to more error. In the case of Within Hands' Reach, pinpointing a position is divided into three tasks:

- Closing in roughly on the area using the giant hand. This movement do not need high precesion and has a large target area (TA) -> faster time (Fitts’s law).

- Creating a mental map of that large area on the giant hand to its physical equivalent on the real hand. Predicting the mapped position (MP) on the real hand of the target positon (TP) in the VE based on the relative position of (TP) wrt (TA). This is a mental and visual task. We could argue that it takes most of the interaction time as it needs mapping distances between the real and virtual world. Also, since the mapping is done using the scale “real hand -> giant hand”, it is subject to more error and thus will contribute more to the trial and error step as described in “Fitt’s law”. A formal study should be performed to test such hypothesis.

- Last step, moving one finger from the second hand to (MP). Here, it could be argued that a good amount of interaction time gain is possible. The movement is no longer based on visual cues but is driven by a sense of proprioception following the second stage (mapping).The user has both visual and kinaesthetic inputs that guide the hand’s movement.

IV\ State of the art:

References:

[1]Bluff, Andrew, and Andrew Johnston. ‘Don’t Panic: Recursive Interactions in a Miniature Metaworld’. In The 17th International Conference on Virtual-Reality Continuum and Its Applications in Industry, 1–9. VRCAI ’19. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1145/3359997.3365682.

[2]Azai, Takumi, Mai Otsuki, Fumihisa Shibata, and Asako Kimura. ‘Open Palm Menu: A Virtual Menu Placed in Front of the Palm’. In Proceedings of the 9th Augmented Human International Conference, 1–5. AH ’18. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1145/3174910.3174929.

[3]Gustafson, Sean, Daniel Bierwirth, and Patrick Baudisch. ‘Imaginary Interfaces: Spatial Interaction with Empty Hands and without Visual Feedback’. In Proceedings of the 23nd Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, 3–12. UIST ’10. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1145/1866029.1866033.

[4]Gustafson, Sean G., Bernhard Rabe, and Patrick M. Baudisch. ‘Understanding Palm-Based Imaginary Interfaces: The Role of Visual and Tactile Cues When Browsing’. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 889–98. CHI ’13. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1145/2470654.2466114.

“Don’t Panic: Recursive Interactions in a Miniature Metaworld”.

In this article, the authors proposed a new interaction technique called Metaworld where the user is presented with “a miniature model of the very virtual world that they are inside”. I find this meta element very interesting. The idea of mapping a space onto a scaled down version of it that we insert into the space itself has a lot of merits. First, remote interaction becomes possible without the need to couple it with a locomtion technique. Second, the visual display of the miniature makes the experience more immersive and allows the user for better control. Within Hands' Reach explores a similar mechanism with the display of the giant hand in the virtual environment. The major difference is in fact that the miniature metaphor is more subtle as the mapping is done on the real hand and we display a giant hand for a reference. This aims at avoiding loss of presence as the user’s focus is now directed towards the VE and not toward the miniature.

Open Palm Menu: A Virtual Menu Placed in Front of the Palm

In this article, the authors adresses a different issue. The solution they’re proposing regards the design and display of a menu in a VR context. The menu is defined as an extension of the user’s hand. The buttons are displayed on the air and follow the open palm of the user. They can be clicked used a finger form the other hand. Although the goal is different, there is one aspect of this technique that attracted my attention and that is this interaction between both hands in order to perform a task. The menu being an extension of one hand, the interaction space becomes defined relatively to it. This is an aspect that is shared with the Within Hands' Reach technique.

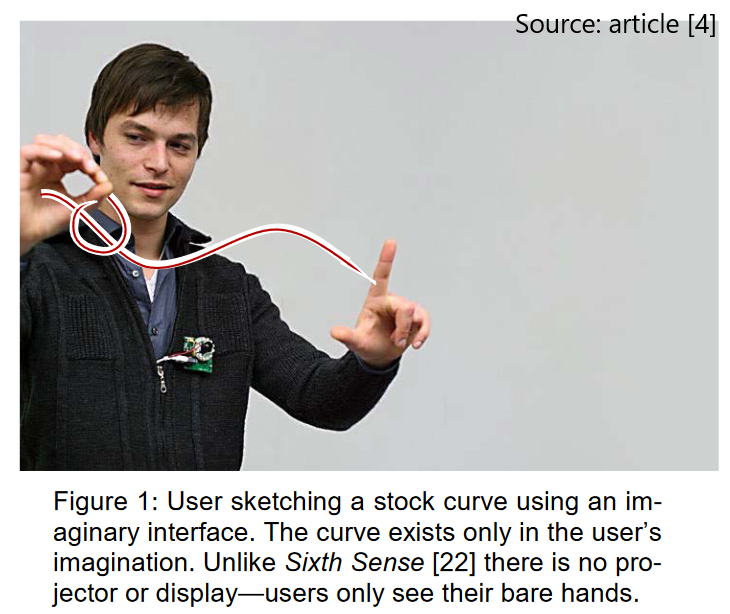

Understanding Palm-Based Imaginary Interfaces: The Role of Visual and Tactile Cues when Browsing

Sean Gustafson et al. worked on developping the concept of imaginary interfaces. These are “screen-less devices that allow users to perform spatial interaction with empty hands and without visual feedback”. The user can define an area of interaction with one hand and use the other one to point and perform actions. What I found interesting in the context of my project was the way this concept incorporates the user’s imagination and short-term memory into the interaction. A second important thing to note is that the work in paper [3] suggests that such systems can “replace conventionally displayed feedback on a screen “ and the further study in paper [4] on the special case of “palm-based imaginary interfaces “ provides a better understanding of why they work. Although Within Hands' Reach does offer a visual display of the normal-sized hands in the VE as well as the giant hand, it still relies on the user to map the relative position of the target object to the giant hand and to imagine and perform the movement of a finger to locate the position on their real hand. Thus, these papers present good arguments for the validity of the new interaction technique proposed here.

V\ Implementation:

1) Setting up a unity project integrating the oculus SDK

The oculus documentation has a detailed description of the different configurations needed to run an app on their headset. You can find it by following this link Oculus Developer Doc. I will note here the most important steps:

- Set Up Oculus Headset: pairing it with your account.

- Install Unity Editor and add the appropriate unity version: for this project, I used the 2002.3.18f1 uinty version and added the Android Build Support.

- Enable Device for Development and Testing: Activating Developer Mode, switching to an android plateform and selecting the correct run device.

- Create a Unity 3D project and importing the Oculus Integration Package.

- Configure the correct build settings.

The project is set. All I needed to do next was to set correctly an OVRCameraRig and two OVRHandPrefab(s) in order to have a functional project with active hand tracking.

2) Implementing a first iteration of the giant hand

I found that the simplest way to reach this goal is to add and scale a third OVRHandPrefab object named GiantHand. The gesture handtracking being automatically active for this new hand as it contains the OVRHand component, all I needed to manage was its transform. To do that, I added a new GameObject called MovementHandler and attached a script to it that retrives the transform of the small right hand, filters some of the degree of freedoms then applies it to the giant hand.

P.S: This iteration of the giant hand consider only the rotation values.

Due to the large scale of the added hand, I needed to make its presence in the user’s field of view less imposing. For that, I decided to translate it halfway under the ground and to use an oculus specific shader that allowed me to tune down the texture’s alpha value. I consider it as a sufficient solution for the current work progress.

At this stage of the project, the user can observe a giant hand in the scene or more so under the scene with only the fingers appearing when flexed. This prototype is still lacking an interactive context, so that’s where I headed next. I considered the simple case of spawning cubes in the scene by pinpointed the position in on the small right hand and have them appear in the equivalent position with regard to the giant one.

You can check the following demo before going throught the implementation details.

To make the pinpointing more easy and to take into consideration the errors in hand tracking, I introduced a small pointing stick glued to the small right hand’s index tip. This pointing stick is a box GameObject with a script attached to it handling the collisions with the left small hand. In this script, I retrieve the collision position relatively to the left small hand and transpose that hand relatevely to the giant hand that I retrieve the world position of that transposed position. This small mechanism can actually be generalized to any type of interaction as it simply allows me to deduce the inteded position of interaction.

I provide below the code for the collision management:

public class CollisionHandler : MonoBehaviour

{

public GameObject giantRightHand;

public GameObject cubePrefab;

private void OnTriggerEnter(Collider other)

{

OVRSkeleton giantRightHandSkeleton = giantRightHand.GetComponent<OVRSkeleton>();

Vector3 localCollisionPos = other.transform.InverseTransformPoint(other.ClosestPoint(transform.position));

foreach (OVRBone bone in giantRightHandSkeleton.Bones)

{

string capsuleName = OVRSkeleton.BoneLabelFromBoneId(OVRSkeleton.SkeletonType.HandRight, bone.Id) + "_CapsuleCollider";

if (capsuleName.Equals(other.name))

{

GameObject a = GameObject.Instantiate(cubePrefab);

Vector3 newPos = bone.Transform.TransformPoint(localCollisionPos);

newPos.y += 4;

a.transform.position = newPos;

a.name = "Cube" + bone.Id.ToString();

}

}

}

}

3) Second iteration: Using two sensors (Oculus hand tracking feature + Leap motion)

One major issue that I faced with the current implementation is occlusion between the hands. The core idea of this technique is based on the interaction between a finger from one hand and the second hand. Such occlusion situation could not be avoided and thus an improvement on the tracking level was needed.

To solve this problem, I tried to use two differnt tracking systems and to “merge” the data I get into a coherent and synchronous pair of skeletal hands. For that, I decided to use a leap motion sensor coupled with the hand tracking feature of oculus quest.

![]()

At this stage, the things I needed to implement are:

- A hand Gamobject with

- a bone structure close to both input bone structures

- some display feature (capsules for each bone or a skinned mesh renderer)

- a way to set colliders to detect when a user is pinpointing an area on their hand

- A way to read bone positions from a leap motion hand

- A way to read bone positions from a the oculus tracking system

Deciding on the final bone structure:

After looking carefully at the different prefabs I got from the leap motion (LP) package and the oculus integration one, I ended up working with a prefab I found in one of the example scenes of (LP) called “Attachment hands”. It comes with all the necessary scripts to have a moving pair of hands that follow the (LP) sensor data and capsules for each bone for the display. I chose this one because it has a simple interface where you can precise with bones you want to keep in the model. I tried to have something very close to the bone structure that the oculus hand tracking works with. I ended up with the following one:

I added to the scene an empty gameobject Output Hands that hold a left and right hand version of this structure.

The giant hand:

This was the easiest step. Since the leap motion sensor is the most trustworthy one when it comes to the base hand (the one on which we map the VE), I used LeapHandController prefabs that comes with the leap motion provider component, a hand model (bone structure + skinned mesh). All I hand to do was to placed a little bit under the floor and to scale it up.

Reading the correct data:

To manage the different input data streams (translations rotations), I created an empty gameObject called MovementHandlerSk and attached to it a two version (left and right) of a script HandleMovementSkeleton. This script will read input values, deduce the output values and apply it to the output gameObject.

public bool isRight;

public GameObject inputOculus;

public Transform inputLeap;

enum TrackingState { OUT, CONTINUITY, NEW_VALUES };

TrackingState leapTrackingState;

TrackingState oculusTrackingState;

public Transform OutputHand;

To store the current data, I worked with Dictionaries using the name of the bones as keys. The keys follows the nomenclature as used in the “Attachment hands” prefab of (LP).

What I needed then, is a way to read the correct translation and rotation data of each bone from both the leap motion and the oculus tracking systems.

- For the (LP) data, it’s straightforward, I just had to add a copy of the “Attachment hands” prefab as my Leap Input Hands gameobject. I deleted the display capsules. HandleMovementSkeleton keeps a reference of such the corresponding hand as a transform variable inputLeap. I can then access recursively its different children to acess each bone.

void ReaDLeapData()

{

if (leapTrackingState != TrackingState.OUT)

{

foreach (Transform inputchild in inputLeap.GetComponentsInChildren<Transform>())

{

if (outputBoneNameToOculusBoneId(inputchild.name) != BoneId.Invalid)

{

Vector3 newPos = inputchild.position;

Quaternion newRot = inputchild.rotation;

positionLeap[inputchild.name] = newPos;

rotationLeap[inputchild.name] = newRot;

}

}

}

}

- For the oculus data, it was a little bit tricky. First, to ensure the same mapping for the oculus data, I use a simple hash function outputBoneNameToOculusBoneId. This function will serve also as a away to discard any bone that does not exist in the output structure (it returns BoneId.Invalid in that case). Then I iterate over each output bone, I then iterate over all the bones as given by the oculus OVRSkeleton component, I find the one that matches my output bone, and read the values. This was not enough since the bones are not structured the same, I needed to apply some correctional terms to have the correct behaviour.

void ReadOculusData()

{

if (oculusTrackingState != TrackingState.OUT)

{

foreach (Transform outputchild in OutputHand.GetComponentsInChildren<Transform>())

{

BoneId currentID = outputBoneNameToOculusBoneId(outputchild.name);

if (currentID != BoneId.Invalid)

{

foreach (OVRBone bone in inputOculus.GetComponent<OVRSkeleton>().Bones)

{

if (bone.Id == currentID)

{

Vector3 newPos = bone.Transform.position;

Quaternion newRot = bone.Transform.rotation;

Vector3 axisForward = newRot * Vector3.forward;

Vector3 axisUp = newRot * Vector3.up;

if (!isRight)

newRot = Quaternion.AngleAxis(-90, axisUp) * Quaternion.AngleAxis(180, axisForward) * newRot;

else

newRot = Quaternion.AngleAxis(90, axisUp) * newRot;

if (outputchild.name == "Palm")

{

newPos += 0.05f * (newRot * Vector3.forward);

}

positionOculus[outputchild.name] = newPos;

rotationOculus[outputchild.name] = newRot;

break;

}

}

}

}

}

}

I also added an enum type to keep track on the state of each type of sensor. It makes sure that we’re not reading unavailable data. It also gives an idea on whether we have a continuous stream of data or whether we lost tracking the previous frame. I will not go into more details for this feature as ended up not using it.

Result: two read functions that updates the following Dictionaries. The keys are the name of each bone.

Dictionary<string, Vector3> positionLeap;

Dictionary<string, Vector3> positionOculus;

Dictionary<string, Quaternion> rotationLeap;

Dictionary<string, Quaternion> rotationOculus;

Moving the output hands:

The goal here is to assign a new position and a new rotation to each output bone.

I started by checking the current tracking state. skip to the next frame if we have no data, otherwise, I call the two read functions.

leapTrackingState = UpdateTrackingState(inputLeap.gameObject.activeInHierarchy && leapConfidence > 0.5f, leapTrackingState);

oculusTrackingState = UpdateTrackingState(inputOculus.GetComponent<OVRHand>().IsTracked && inputOculus.GetComponent<OVRHand>().HandConfidence == OVRHand.TrackingConfidence.High, oculusTrackingState);

if (oculusTrackingState == TrackingState.OUT && leapTrackingState == TrackingState.OUT)

{

return;

}

ReaDLeapData();

ReadOculusData();

I then calculate the center of mass of each set of hands -> centerOfMassOculus & centerOfMassLeap. This is usefull to discard any translation that is not related to the movement of the user’s hand. Also, it helped me solve a problem I faced with the leap motion “Attachment hands” prefab. It is automatically attached to the leap provider of the giant hand. And since the giant hand is scaled up and under the floor, the input leap hands data needed to be scaled down and moved to the correct position (in front of the user). In this case, I substract from the leap position centerOfMassLeap, then scaled down and add centerOfMassOculus. (centerOfMassOculus being the most correct one).

Having all this set, I then iterate over all the bone children of OutputHand and calculate the target values to be assigned as determined by each tracking system (Leap motion & Oculus). For the right hand (the one used to point and interact), I use mainly the data I get from the oculus. For the base hand, I use mostly the data I get from the leap motion.

foreach (Transform outputChild in OutputHand.GetComponentsInChildren<Transform>())

{

if (outputBoneNameToOculusBoneId(outputChild.name) != BoneId.Invalid)

{

Vector3 targertOculus = positionOculus[outputChild.name];

Vector3 targetLeap = 0.11f * (positionLeap[outputChild.name] - centerOfMassLeap) + centerOfMassOculus;

Vector3 targetposition;

Quaternion targetRotation;

if (isRight)

{

float coef = Mathf.Max(1, 1.2f - leapConfidence); // 0 = use leap only; 1= use oculus only; 0<t<1 : lerp between two values

targetposition = Vector3.Lerp(targetLeap, targertOculus, coef);

targetRotation = Quaternion.Slerp(rotationLeap[outputChild.name], rotationOculus[outputChild.name], coef);

}

else

{

float coef = Mathf.Min(0, 0.3f - leapConfidence); // 0 = use leap only; 1= use oculus only; 0<t<1 : lerp between two values

targetposition = Vector3.Lerp(targetLeap, targertOculus, coef);

targetRotation = Quaternion.Slerp(rotationLeap[outputChild.name], rotationOculus[outputChild.name], coef);

}

outputChild.position = targetposition;

outputChild.rotation = targetRotation;

}

}

Performing tasks:

The main feature of Within Hands' Reach is the ability the pinpoint using a finger a position in a virtual “room” of control. Using this mechanism, one simple way to interact with the environment is to associate with each finger a certain task. To demonstrate this technique, I worked on two different types of action:

- Activating an object: using the index finger the user can hit an area on their hand and the closest corresponding object will be activated.

- Spawning an object: using the pinky finger the user can hit an area on their hand and the closest corresponding object will be activated.

4) Developing a demo application:

The demo is a simplified version of the classic game “Whac-A-Mole”. The player is presented with a grid of tile. Each tile contains a mole (a cube) that appears and disappears randomly. The player has to hit the moles to increase the score.

I started by creating this prefab Tile. It contains two components: the ground (brown) and the mole (green).

I created a script MoleTile that I attached to this prefab to manage its behavior. This script simulates a simple state machine. I defined three states:

- DOWN: y=-1

- NORMAL: y=1 & color=green

- SUPER: y=1 & color=red The last two are different versions of the UP state where the player should hit the mole.

public enum MoleState { DOWN, NORMAL, SUPER};

public MoleState currentState;

The events are activated at fixed time steps or when the player hit a mole.

VI\ Potential improvements:

- Find a better bone structure that matches better both tracking system.

- Use a different leap motion prefab that has a seperate center of mass that you can move to match the one we get from oculus.

- A different approach would be to avoid pointing directly with a finger. Instead, a pen can be fixed on an oculus controller and a virtual version of that pen in the environment follows the rotation and position of the controller. The pen can be used to point areas on the second hand. One interesting point to note is that article [4] argued that the active haptic feedback you get from the finger do not contribute that much in the information the user get. The passive feedback the user get on the palm of the second hand is more informative and helps the user situate better which area was pointed. Thus, using a pen could be a good idea to avoid occlusion issues.